“They came, they served. Elles sont venues, Elles ont servi.” The Grey Nuns exhibit was created to celebrate the enduring legacy of the Sisters of Charity in the Lewiston-Auburn community.

The first Grey Nuns arrived in Lewiston in 1878 at the request of Reverend Pierre Hevey, a Roman Catholic priest and native of Saint Hyacinthe, Quebec who saw the dire needs of the local working poor, the majority of whom were from French-speaking Canada. Although an influx of French-speaking immigrants to the industrial cities of Maine arrived in the 1860s, French Canadians seeking work came in increasing waves from the 1880s until the 1930s. The Franco American population of Maine was unique among immigrants to Maine in this period because this was a North American group that remained in close proximity to the country of origin.

Even more importantly, Maine’s Franco Americans were able to build a community within a community, establishing parishes, schools, hospitals, newspapers, credit unions and other institutions of their own, permitting them to maintain their mother tongue, their culture of origin, and their own values. Unlike immigrant groups who often assimilated into English-speaking society after the first generation, Franco Americans continued to speak and live in French for three, four, or even five generations. As historian Mark Paul Richard has shown, Franco-Americans negotiated their identities in unique ways, challenging and changing the cultural environment of the twin cities.

The first French-speaking immigrants to New England were men who hoped to remain only as long as it took to amass savings from factory wages to return home to Canada, but by the late 1870s more and more families arrived to settle in “Little Canadas” like the one in Lewiston. With them came French-speaking Canadians who saw opportunities to settle as well: merchants and other entrepreneurs, doctors and lawyers, and members of religious communities who served the spiritual, educational, and corporeal needs of the Franco Americans.

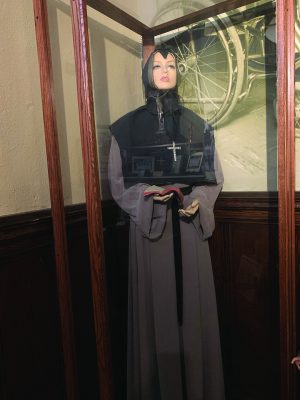

In 1878, when Father Hevey saw the rising need for aid to the people of Lewiston’s Little Canada, he turned to the Sisters of Charity of Saint Hyacinthe, Québec for good reason. While many Roman Catholic religious orders eventually came to Maine to work among the state’s Franco Americans, the Grey Nuns’ mission of service to the poor distinguished this order of religious women. The order was founded in 1744 by Marguerite d’Youville, who was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church as its first Canadian-born saint in 1990. Marguerite

d’Youville’s own life experience as a fatherless child, a neglected wife, a widow and single mother informed the mission of the Sisters of Charity: to serve the poor in whatever way necessary. In her lifetime, she worked with disabled soldiers, the elderly, the mentally ill, foundlings and orphans.

When the Sisters of Charity of Saint Hyacinthe, Québec accepted Father Hevey’s request, they were willing to take on new tasks such as education in addition to their work as sister-nurses. The Grey Nuns grew and changed as the community developed.

Although the religious beliefs of the Grey Nuns are not the primary focus of this exhibit, religious faith and culture are deeply embedded. In order to tell the story of these women and those they served, some attention must be paid to the cultural significance of their faith and its impact on patient care. In her history of the Grey Nuns of Lewiston-Auburn, “The Quiet Revolutionaries, How the Grey Nuns Changed the Social Welfare Paradigm of Lewiston, Maine,” Susan P. Hudson, Ph.D., who served as a consultant for the exhibit, demonstrates that the Grey Nuns developed new paradigms for patient and family care at institutions like St. Mary’s hospital, the Healy Asylum, and the Maison Marcotte. Her research uncovered important statistical and documentary evidence of differences in patient care between St. Mary’s General Hospital and Central Maine General Hospital grounded in cultural and faith tradition. The exhibit builds on Dr. Hudson’s work through analysis of qualitative evidence

about the Grey Nuns’ service, largely taken from oral histories.

The heart of the exhibit “They came, they served. Elles sont venues, elles ont servi” is a collection of interviews with members of the Sisters of Charity by Annette Bourque, former director of marketing for St. Mary’s Hospital and the Sisters of Charity Health System. The interviews represent important documentary evidence of the Grey Nuns and their work. These core interviews are enhanced by a collection of interviews from local area residents about their interactions with the Grey Nuns and their experience with the services the sisters provided. While the exhibit celebrates the work of the Grey Nuns, it is also designed to provide a balance of perspectives on the past and the present, and on this model of healthcare and social services and others. This exhibit is a timely reminder that past groups of immigrants like the Franco Americans faced challenges in maintaining their cultural identity and values not unlike those challenges faced by Somalis, Togolese, Rwandans and other New Mainers in the present. Moreover, social services were equally as important to the support of newly arrived people in the past as they are in the present, however different their configuration in specific time periods.

The lens of gender enables us to view these women as competent and strong professionals who provided many essential social services from a gendered as well as cultural perspective. The Healy Asylum in Lewiston, for example, needs to be considered as much more than a traditional home for orphaned children. It served as a refuge from domestic violence for some, and as child care center designed to relieve mothers of newborns of some of the childcare and household demands placed on them. The heart of the story that the exhibit tells involves the everyday connection of the nuns to families in the local area, as they served as its “backbone,” thus lending an important social infrastructure to the Franco American community that was distinctive to this culture. Language and religious faith must also be considered.

The exhibit is bi-lingual, with either subtitles or voice-overs used on taped footage.